Missionary Position

Sky documentary unearths the back story to last season’s fairytale

A little over twenty years ago, prominent Clarets follower and long-time tormentor of the Fourth Estate, Alistair Campbell was sat by the side of his then-boss, Tony Blair during a routine Downing Street press briefing. One of the assembled hacks asked a gently probing question about Blair’s religious faith. Smelling potential trouble, Campbell grabbed the microphone before Saint Tony could begin his inevitably eloquent reply and said bluntly: “We don’t do God”, giving the hack a sorry shake of the head as penance.

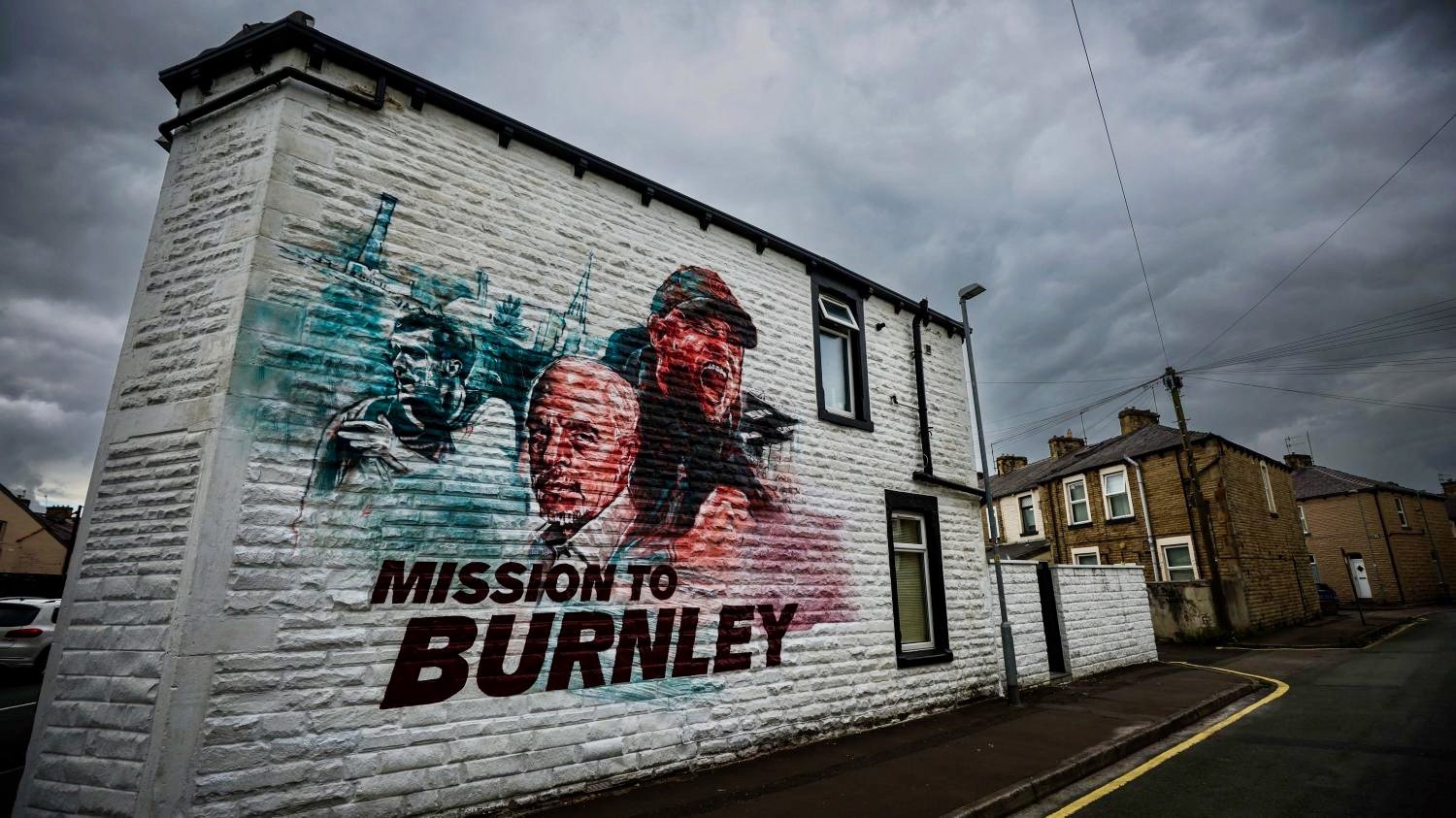

It’s unlikely Alistair was consulted by Alan Pace, Mike Smith, Stuart Hunt, Morgan Edwards and John Dewey, principals in ALK Capital (so named after Pace’s three daughters) and proud owners of Burnley FC since 2021. The first clue to the ‘mission’ is in the title sequence, a montage of down-at-heel Burnley scenes contrasting with the gilded Angel Moroni atop the Preston Mormon Temple.

The opening shots feature the four gentlemen, cavorting on a football pitch somewhere bucolic near the Lancashire coast. Pace’s audio overdub makes clear that this group has worked together for a long time, wanted to buy a football club and are all members of the Church of Latter Day Saints (LDS) or Mormons. No shilly-shallying around the facts: this is who we are and what we are doing.

The resumés of all the directors suggest eminent suitability as owners, having clearly been successful in the higher echelons of global finance and sports management. All look and sound the part with excellent communication skills ‘to camera’ and exude that quiet, driven authority of those who are familiar and comfortable with success as the natural course of events. The blunt disclosure of the transaction's financial terms is unflinching but stops short of explaining the rationale behind leveraged finance. It’s an accepted paradox amongst financiers that you should never invest in a business with your own money if nobody will lend it to you. And if you can find someone to lend to you, why invest your own? Essentially, they followed this playbook, and while it might cause much wailing and gnashing of teeth amongst the fan base, it is how this world works and the point needed to be made.

But it’s Pace’s back story that answers the question: “Why Burnley?” It transpires his father was a missionary for the Mormons in the 1960s, following a long tradition of LDS presence in the area dating back to 1837. Viewed through this lens, Pace is simply carrying on the family business. But this time, the mission is the transformation of an old-school Northern football club to a global sports media property, managed with a steely-eyed corporatism to within an inch of its life.

Burnley was one of the few survivors at the higher levels of football that followed the tradition of ownership by a local grandee and thus being presided over with a degree of patrician authoritarianism. So the exam question posed is: Does the club and its followers want to see Light & Truth or is the emotional attachment to tradition stronger, regardless of success on and off the pitch?

What plays out over the four episodes is a chronological canter through a narrative arc familiar to readers of STWHA, but probably not for the target ALK has in their sights. Helpful subtitles abound informing us that Lancashire (like London) is indeed in England. And just when you thought this was for the benefit of the folks back home in Salt Lake City, this too gets subtitled as Utah. This is brand-building on a global scale, reaching out to an audience in remote parts of the world - Man U style - who will never visit the UK or the USA, but might just buy a replica shirt.

Starting with the departure of Sean Dyche and the desperate scramble for survival that follows, Mission to Burnley tells a tale of resurrection from the ashes that would probably be rejected as too fanciful if pitched as a film script. It’s an odd counterpoint to the recent ‘Bank of Dave’ movie where the premise of this was eminently plausible, yet ended up as a significant and needless distortion of fact.

As the final whistle blows after the defeat to Newcastle and relegation, the camera captures well the complete isolation of Pace. He tries to put a brave face on it with his slightly high-pitched, sniggering Muttley-like laugh as commiserations are offered, one after the other. But the devastation is etched into his face. He knows it is critical for him to show strength while everyone’s eyes bore into him as the agony gnaws away inside.

Addressing the glum commercial staff, Pace is open and honest with them and confesses the toughest aspect of sports management is not being able to influence what happens on the pitch. Asked about the search for a new manager, he says they are close but clams up on details. In another exchange with a fellow director, he wrestles with the new appointment. Faith then hoves into view as he says the decision-making process needs “more prayer”. Elsewhere, one of the others jokes with him, without rancour, that they must be viewed as a “bunch of weirdos” by the rest of the footballing world for their beliefs.

Into this quagmire strides the colossus that is Vincent Kompany, nearly bumping his head as he enters Barnfield for the first time. Articulate and cogent, his perfect English - spoken with a Northern European accent to the press and investors - is that of the mayor of a medium-sized Belgian town. Only during his dressing room speeches does he lapse into potty-mouthed Mancunian, redolent of the thicker of the two Gallagher brothers, channelling Al Pacino’s stirring rants in ‘Any Given Sunday’. While Kompany’s record as player and charisma were never in doubt, his grasp of complexity as he scans a sea of graphs and data, while juggling internal politics and media optics suggests a considerable intellect at work. This, combined with the evident intuition he has with his players, makes him a compelling subject

But for followers of Burnley, it’s the details where the program excels. In one scene we hear bluff Chief Operating Officer Matt Williams shred an irritating agent during an amusingly bracing phone call on transfer deadline day. In another, he takes us through the on-boarding process of a foreign player. This involves a visit from a Home Office official before a battery of physical tests, every detail being precisely measured and recorded. The scene where ink is put on paper gives a few tantalising glimpses of the minutiae of player contracts: Byzantine constructs that feature Substitution bonuses (different if the player is used or just sat on the bench); league points attained that trigger further payments and so on…

In another scene, new investor and former US football star JJ Watt (one of few Human Beings to make Kompany look a tad puny…) chats with Vincent about preparation during match week. JJ recounts daily, five-hour whiteboard sessions while Kompany bemoans struggling to get his lot to sit down for thirty minutes at a time.

The show features Ashley Barnes in a few notable cameos. After the first team talk, Barnes and Kompany seem genuinely happy to be on the same side at last after various blood-curdling encounters on the pitch over the years. During interview, Kompany warmly praises Barnes for becoming an unexpected mentor for younger players, the tone chilling as he explains that he had told Barnes straight he was not part of next season’s plan. But the defining image - possibly the leitmotif for Barnes’ career - is when he scores against Blackburn and then chucks the goalkeeper into the back of the net for good measure.

Not all the glimpses behind the curtain work. Some of the artful HD drone footage makes Alan Pace resemble Alan Partridge in a string of trite, visual metaphors. We have Alan striding purposefully up a ridge in the Lake District (achievement in the face of adversity…); Alan canoeing on a perfectly still lake (the loneliness of leadership…) and a sequence of him and a pal gadding about on snowmobiles through a stunning Utah landscape (competitive but collegiate and one of the boys…). It's all lovely to behold and in keeping with the glossy production values in evidence throughout but adds little to the narrative.

So did the Mission succeed? On the evidence so far, they appear to have got the big calls right. I’m more persuaded by sleek professionalism and sense of purpose as the root causes for last season's success than the alternative view suggested by one of Pace’s daughters. With unshakeable confidence in an impressively unblinking interview, she decrees it an example of divine orchestration.

This season’s early results severely test both theories and suggest that ‘The Biggest Gap in the Football World’ between Championship and Premiership might not be the hyperbole it seems. At this early stage, the next eight months look like a return to the traditional, attritional slog.

A lingering possibility is the Burnley faithful actually prefer it this way, particularly if the alternatives include drastic change and junking of tradition. There is a point where struggle becomes baked into the psyche, be that of a person, an organisation or a community. When that becomes the norm, accepting success is as uncomfortable as struggle is to those largely unaccustomed to it.

An intriguing line from Lukas Mattson, the ghastly, Swedish media-tech bro in HBO’s ‘Succession’ was "Success doesn't really interest me anymore. It's too easy: analysis plus capital plus execution. Anyone can do that. Now failure: that’s fascinating.”

Winning continuously has a certain blandness to it. Man City are the perfect case to prove Mattson’s algorithm. Remove one of the inputs and that’s when potential jeopardy appears and that perfect Negroni of brain chemicals (two parts Dopamine and Serotonin, one part Adrenaline) is served. Do City fans ever get to experience this lurch between elation and despair? Rarely, if ever and I suggest their lives are - on the whole - duller as a result.

ALK don’t exhibit Mattson’s stratospheric arrogance nor his ghoulish, billionaire’s schadenfreude. Quite the opposite: they appear likeable engaged, engaging and humble. However, they do expect to continue on the trajectory they have clearly become accustomed to, dealing calmly with obstacles as they arise, but maintaining upward progress overall. All that’s needed is a plan and to have faith. And they have a lot of that.