Mussel Shoals

31 May 2024

3614 North Jackson Highway is in the poor area of a poor town in Northern Alabama. Pavements are crumbling, there’s a rusting Airstream caravan and the prevailing whiff is like the stairwell at an NCP car park.

I’m crammed into the vestibule of a squat, concrete, former coffin showroom with nineteen others, waiting for a tour of the legendary Mussel Shoals Sound Studio.

You might not know of Mussel Shoals but it has contributed to the soundtrack of your life as you will have hummed along to innumerable songs crafted in this unprepossessing building. This group of twenty I’m part of, along with the one before it, and the four others today are interested to find out what makes it so special.

A former studio manager, Tayler, is our host for the tour. He explains how, after a rent disagreement in 1979, the studio had moved elsewhere. The building was then used as storage space for an electrical retailer and had fallen into disrepair. It was then bought for a song (sorry) in 2013 by the foundation that now owns it. This coincided with the release of a documentary, seen by Andre Romell Young, better known professionally as Dr. Dre, an American record producer, rapper and headphone mogul.

Appalled that an important chapter in popular music’s history was in danger of being erased, Young dispatched lawyers to Alabama to offer a $1 million grant for the restoration of the studio. The proviso was it had to be returned precisely to as it was in 1979, right down to a horrible, orange shag-pile carpet in the ‘secret’ room.

This is accessed through a door, concealed in the naff wood paneling in the basement, and served as an illegal bar for thirsty musicians as the county was dry in the 1960s and 70s.

The majority of the tour is in the studio itself. Tayler points out photographs, instruments and other features while recanting a stream of anecdotes and reminiscences about the cast of characters.

He pauses only to reflect when the person he’s talking about has died. About only one is he taciturn: Bob Dylan. “Small. Very quiet. Strange”, is all he has to say.

Artists gravitated to Mussel Shoals for one or more of three specific reasons, and one general one.

First, the four extraordinarily talented musicians who founded the studio were available for hire and could play in any style and deliver exceptional results, quickly.

Second, the unique sound of the space where the recording took place. This is a product of using a room intended to show off pine boxes rather than make music and made-good with cheap, off-cut materials to dampen echoes, and the sound of the frequent Alabama rain, pounding on the tin roof. Implausibly, this resulted in a unique sonic thumb-print that resonates subliminally with millions of people.

Lastly, the ‘desk’ used to mix final versions of recordings just had a particular tone to it, compared to others of the same model and vintage. This too has been restored so it sounds just as it did 45 years ago, and contemporary artists still flock to use it. Only last week, a Dutch heavy metal band was here, says Tayler, barely concealing a wince.

But the singular purpose for most artists was to make a hit record. This studio was adept at churning them out and has produced more Number 1s than any other apart from Motown. What it did offer was seclusion and a lack of distractions. All the artists stayed at the Holiday Inn in Florence for the simple reason there was nowhere else nearby. And Florence had no bars, restaurants or night clubs. Nothing.

The locals apparently thought these peacocks that strutted around the town looked a bit odd, but nobody knew who they were so generally left them alone. Intriguingly, Tayler paints a picture of a work ethic that is a world away from the fire-wheeling hedonism of the 1970s music industry that is the popular myth. These were diligent, hard-working professional musicians who took their art extremely seriously and wanted to create the best work they were capable of.

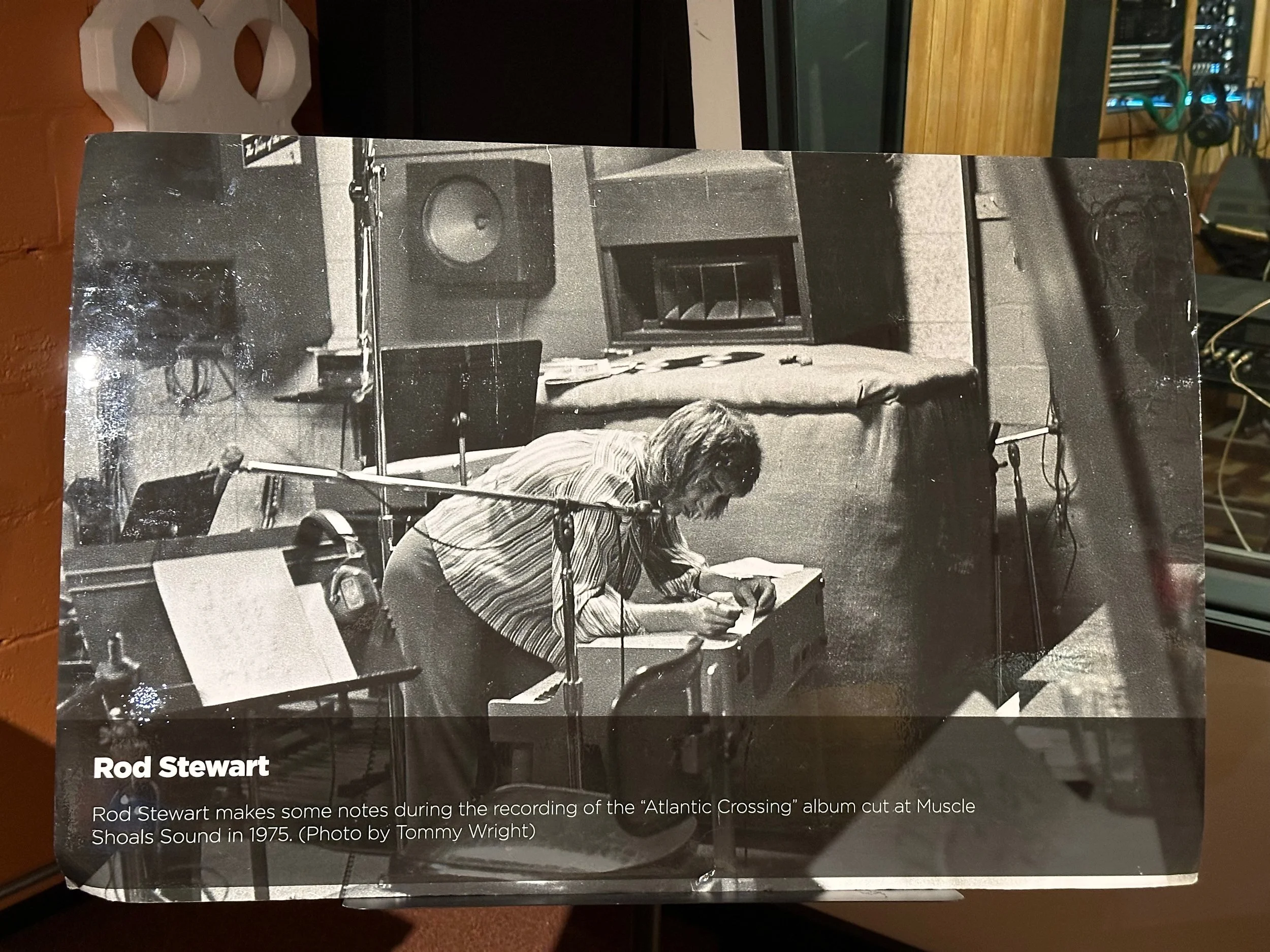

There’s a music stand with large photograph of Rod Stewart, making notes during the 'Atlantic Crossing’ sessions in 1975.

I mention to Tayler that it was listing to this album on my Dad’s prized Wharfedale DD1 headphones, while reading the album sleeve notes, when I first realised how good music you’d normally hear on a tinny radio could sound. After that, I kept seeing the Mussel Shoals name crop up on other records.

“Yes”, he says nodding wistfully, “we put the picture there as that’s where he liked to stand when singing, so he could see into the control room.”

A friend, colleague and talented musician with a scientific mind, once commented to me that music is as close to magic as he is prepared to accept exists.

A visit to Mussel Shoals maintains this incantation, offering only the slightest glimpse of what lies behind the curtain.

And 'Atlantic Crossing' still sounds great, fifty-years on next year…